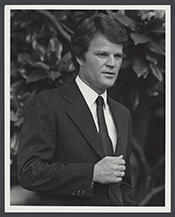

Representative Charles Elson Roemer

Here you will find contact information for Representative Charles Elson Roemer, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Charles Elson Roemer |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Louisiana |

| District | 4 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | January 5, 1981 |

| Term End | January 3, 1989 |

| Terms Served | 4 |

| Born | October 4, 1943 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | R000384 |

Editorial and Source Notes

Last reviewed: January 1, 2026

We prioritize official government pages and published records. Information can change after publication.

Primary records and source links are added as they are verified.

Report a correction: see our Editorial Policy.

About Representative Charles Elson Roemer

Charles Elson “Buddy” Roemer III (October 4, 1943 – May 17, 2021) was an American politician, investor, and banker who served as the 52nd governor of Louisiana from 1988 to 1992 and as a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1981 to 1988. Originally a Democrat, he was a member of the Democratic Party throughout his congressional service and for most of his gubernatorial term before switching to the Republican Party in March 1991 while serving as governor. Over four terms in Congress, Charles Elson Roemer represented Louisiana’s 4th congressional district and contributed to the legislative process during a significant period in American political history.

Roemer was born on October 4, 1943, in Shreveport, Louisiana, the son of Charles Elson “Budgie” Roemer II (1923–2012) and the former Adeline McDade (1923–2016). He was reared on the family’s Scopena plantation near Bossier City in northwestern Louisiana. His maternal grandfather, Ross McDade, married a sister of the maternal grandmother of James C. Gardner, a future mayor of Shreveport, though Roemer and Gardner were not close politically. Roemer attended public schools and graduated in 1960 as valedictorian of Bossier High School. He then enrolled at Harvard University, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics in 1964, followed by a Master of Business Administration in finance from Harvard Business School in 1967.

Following his education, Roemer returned to Louisiana and worked in his father’s computer business before going on to found two banks, beginning a parallel career in finance and business that would continue throughout his life. His father, Charles E. Roemer II, had been campaign manager for Edwin Edwards in the 1971 gubernatorial race and later served as commissioner of administration during Edwards’ first term as governor, giving Buddy Roemer early exposure to state politics. Buddy Roemer himself worked on the Edwards campaign as a regional leader and subsequently started a political consulting firm. In 1972, he was elected as a delegate to the Louisiana Constitutional Convention held in 1973, serving alongside such Shreveport-area figures as future gubernatorial adviser Robert G. Pugh, future U.S. District Judge Tom Stagg, and former State Representative Frank Fulco.

Roemer first sought a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1978, running in the nonpartisan blanket primary for Louisiana’s 4th congressional district after the retirement of long-serving Representative Joe Waggonner. Roemer criticized the high costs of the Red River navigation program, which Waggonner supported, prompting the outgoing congressman to oppose Roemer’s candidacy. In the primary, Roemer finished third, 1,708 votes behind Democratic State Representative Buddy Leach, with Republican Jimmy Wilson in second place; Leach narrowly defeated Wilson in a disputed general election. Roemer ran again in 1980, once more facing Leach and Wilson, as well as State Senator Foster Campbell. In that primary, Leach led the field with 29 percent, Roemer placed second, and Wilson finished third. With Wilson’s support in the general election, Roemer decisively defeated Leach by a margin of 64 to 36 percent, despite Leach’s backing from Campbell, numerous state legislators, and former Governor Edwards.

Charles Elson Roemer entered Congress in January 1981 as a Democrat representing Louisiana’s 4th congressional district, which includes Shreveport and Bossier City. He was re-elected without opposition in 1982, 1984, and 1986, serving four terms in the House of Representatives from 1981 to 1989. During his tenure, he frequently supported President Ronald Reagan’s policy initiatives and often clashed with the Democratic congressional leadership. In 1981, he joined forty-seven other House Democrats in supporting the Reagan tax cuts, which were strongly opposed by Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill Jr. and fellow Louisiana Democrat Gillis William Long. In 1984, he again broke with O’Neill by supporting Reagan’s request for U.S. aid to El Salvador, which Roemer described as “a freedom-loving country,” and he served as a congressional observer in that nation’s elections. His independence from party leadership led to his being denied a seat on the House Banking Committee; instead, he was assigned to the Public Works and Transportation Committee after voting with Republicans on extending debate over House rules proposed by the Democratic majority. He was associated with the “boll weevil” Democrats and the Conservative Democratic Forum. O’Neill characterized him as “often wrong but never in doubt,” while Roemer criticized the Speaker as “too liberal.” After Roemer left the House to become governor, his administrative assistant, Republican Jim McCrery, succeeded him in representing the 4th district.

Roemer emerged as a candidate for governor in the 1987 Louisiana gubernatorial election, joining a crowded field challenging three-term incumbent Edwin Edwards, whose tenure had been marked by both popularity and ethical controversy. Other major candidates included U.S. Representatives Bob Livingston, a Republican from suburban New Orleans, and Billy Tauzin, a Democrat from Lafourche Parish, as well as outgoing Secretary of State James H. “Jim” Brown. Roemer’s candidacy was particularly notable because of his family’s prior association with Edwards: his father had been Edwards’ top aide and campaign manager during the first Edwards administration but had later gone to prison in 1981 on a conviction related to selling state insurance contracts. Running on a “Roemer Revolution” platform, Buddy Roemer pledged to “scrub the budget,” overhaul education, reform campaign finance laws, and reduce the size of state government, famously promising to “brick up the top three floors of the Education Building.” In a pivotal campaign moment, when candidates were asked if they would endorse Edwards in a runoff, Roemer responded, “No, we’ve got to slay the dragon. I would endorse anyone but Edwards.” His reform message, coupled with endorsements from nearly every major newspaper in the state as the “good government” candidate, propelled him from the back of the polls to first place in the primary with 33 percent of the vote, ahead of Edwards’ 28 percent. Recognizing his likely defeat in a runoff, Edwards conceded on election night and withdrew, effectively ceding the governorship to Roemer without a general election.

Roemer was inaugurated as governor on March 14, 1988. Confronted with a $1.3 billion state budget deficit, he made fiscal stabilization his first priority. Early in his administration, he issued an executive order creating the state’s first Office of Inspector General and appointed investigative journalist William Hawthorn Lynch as inspector general, empowering him to investigate corruption, inefficiency, and misuse of state resources; Lynch held the post until his death in 2004. Roemer named Lake Charles timber businessman and one-year state representative Dennis Stine as commissioner of administration, a position Stine held through the end of Roemer’s term. His first chief of staff, Len Sanderson Jr., a former journalist who had managed Roemer’s gubernatorial campaign, was closely identified with the administration’s reform agenda and helped secure passage of much of its early legislation before leaving the position, reportedly due to injuries from an automobile accident. After an interim appointment, Roemer selected former State Representative P. J. Mills of Shreveport as chief of staff to bring additional legislative experience to the office. Roemer also employed Shreveport political consultant and pollster Elliott Stonecipher.

As governor, Roemer called a special session of the legislature to advance an ambitious program of tax and fiscal reform for state and local governments. He pledged to cut spending, abolish certain programs, and close some state-run institutions. In October 1989, voters rejected several of his proposed tax initiatives in a statewide constitutional referendum, though they approved a constitutional amendment for transportation improvements. Roemer nonetheless pursued policies to raise lagging teacher salaries, provide modest pay increases to state employees and retirees after years of austerity, and strengthen campaign finance laws. He was also the first Louisiana governor in recent history to prioritize environmental protection, appointing Paul Templet as secretary of the Department of Environmental Quality. Templet’s aggressive regulatory stance angered the state’s powerful oil and gas interests, and many of Roemer’s initiatives faced resistance from a legislature dominated by Edwards allies. In 1989, the Louisiana Board of Appeals recommended a pardon for Gary Tyler, widely regarded as a political prisoner and victim of extreme racism during the desegregation of Louisiana’s public schools; despite his own father’s record as an advocate of African American civil rights, Governor Roemer declined to consider a pardon in a racially charged climate in which David Duke was gaining political prominence. Tyler, who had already served 14 years in prison by 1989, remained incarcerated until his release in 2016.

Roemer’s tenure was marked by contentious social and political issues. In 1990, he vetoed a bill sponsored by Democratic Senator Mike Cross and supported by influential Republican Senator Fritz H. Windhorst and Senate President Allen Bares that would have banned abortion even in cases of rape and incest and imposed fines of up to $100,000 and ten-year prison terms on practitioners. Roemer argued that the bill was incompatible with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, a stance that alienated many socially conservative supporters. The legislature overrode his veto by an even larger margin than that by which the bill had originally passed, though in 1991 U.S. District Judge Adrian G. Duplantier ruled that the measure conflicted with Roe and with Planned Parenthood of Pennsylvania v. Casey. Roemer also presided over the legalization of a state lottery and the authorization of riverboat gambling and video poker, initiatives that some reformers opposed. In 1991, with his support, the legislature approved up to fifteen riverboat casinos and video poker at bars and truck stops statewide, although these operations did not begin until after he left office. During this period, Roemer’s personal life drew some attention; he separated from his second wife, the former Patti Crocker, in 1989, and the couple divorced in 1990 after seventeen years of marriage. They had one child, Dakota Frost Roemer, a Baton Rouge businessman who in 2012 married Heather Rae Gatte of Iota, Louisiana. Roemer also faced criticism for hiring a friend to teach “positive thinking” techniques to his staff, including the use of rubber bands on their wrists to discourage negative thoughts.

In March 1991, months before the state’s open primary for governor, Roemer switched his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican, reportedly at the urging of White House Chief of Staff John H. Sununu in the administration of President George H. W. Bush. Roemer had earlier appeared as the Democratic governor-elect at the 1988 Republican National Convention in New Orleans to welcome delegates, an event brought to the city in part through the efforts of longtime Louisiana Republican National Committeewoman Virginia Martinez. His late-term party switch angered many Republicans as well as Democrats. State Republican Party chairman Billy Nungesser opposed Roemer’s move and, failing to cancel a planned endorsement convention, proceeded with an event that Roemer declined to attend. The convention endorsed U.S. Representative Clyde C. Holloway, a favorite of anti-abortion activists, with whom Roemer was then at odds.

The 1991 gubernatorial race featured Roemer, Edwards, former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke, and Representative Clyde Holloway in Louisiana’s open primary. Roemer’s standing was weakened by the controversies and setbacks of his governorship, while Edwards and Duke each attracted highly motivated bases of support. In the primary, Roemer finished third and was eliminated from the runoff. One factor in his defeat was a late advertising campaign funded by Jack Kent, owner of Marine Shale, a company targeted by the Roemer administration for pollution violations; Kent spent approximately $500,000 on anti-Roemer commercials in the final days of the race. The resulting runoff between Edwards and Duke drew national attention. Although Roemer had campaigned on an “Anyone but Edwards” theme, he ultimately endorsed Edwards over Duke, the de facto Republican candidate. Upon leaving office, Roemer predicted that his “unheralded” accomplishments would become more apparent during Edwards’ fourth term and attributed his defeat in part to his alienation of entrenched special interests. As of the 2023 election cycle, he remains the last Louisiana governor to have hailed from the northern part of the state.

After departing the governorship in early 1992, Roemer briefly returned to academia, teaching a course in economics during the spring 1992 semester at his alma mater, Harvard University. He then re-entered the private sector, drawing on his background in banking and international business. Following the conclusion of the 1991 election cycle, he partnered with longtime friend Joseph Traigle, whom he had first met in the late 1960s through Junior Chamber International activities in Shreveport, to establish The Sterling Group, Inc. The firm specialized in the international trade of plastic raw materials between the United States and Mexico, reflecting Roemer’s strong support for expanding Louisiana and U.S. trade with Mexico. Roemer served as chairman of the board, while Traigle was president; Traigle bought out Roemer’s interest in the company in 1997.

In the later phase of his public life, Roemer remained active in national political debates and reform efforts. In the 2012 election cycle, he sought the presidential nominations of both the Republican Party and the Reform Party, emphasizing issues such as campaign finance reform and political corruption. After withdrawing from those contests, he pursued the 2012 Americans Elect presidential nomination, but the organization ultimately decided not to field a candidate because no contender met its minimum threshold of support for ballot access. Roemer then endorsed Libertarian Party nominee Gary Johnson, the former governor of New Mexico, in the 2012 general election. He also served on the Advisory Council of Represent.Us, a nonpartisan anti-corruption organization advocating for reforms to reduce the influence of money in politics. Roemer died on May 17, 2021, closing a career that spanned business, banking, and more than a decade of prominent state and national political service.