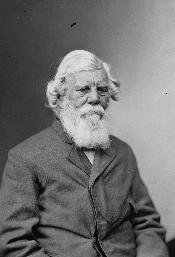

Representative William Aiken

Here you will find contact information for Representative William Aiken, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | William Aiken |

| Position | Representative |

| State | South Carolina |

| District | 2 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 1, 1851 |

| Term End | March 3, 1857 |

| Terms Served | 3 |

| Born | January 28, 1806 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | A000063 |

Editorial and Source Notes

Last reviewed: January 1, 2026

We prioritize official government pages and published records. Information can change after publication.

Primary records and source links are added as they are verified.

Report a correction: see our Editorial Policy.

About Representative William Aiken

William Aiken Jr. (January 28, 1806 – September 6, 1887) was an American statesman, planter, and Southern Unionist who became one of the wealthiest citizens of South Carolina and a prominent political figure in the antebellum United States. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 61st governor of South Carolina from 1844 to 1846 and later represented South Carolina in the United States House of Representatives from March 4, 1851, to March 3, 1857. During his three terms in Congress he participated actively in the legislative process and represented the interests of his constituents at a time of mounting sectional tension. In 1856 he was a leading candidate in what has been described as “the longest and most contentious Speaker election in House history,” narrowly losing the race for Speaker of the House.

Aiken was born in Charleston, South Carolina, the son of William Aiken Sr. and Henrietta Wyatt. His father, an Irish immigrant, was the first president of the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company and a key figure in the early development of rail transportation in the state. William Aiken Sr. was killed in a carriage accident in Charleston and did not live to see the town of Aiken, South Carolina—named in his honor—develop. Raised in a prosperous and politically connected environment, the younger Aiken was educated in Charleston and then attended the College of South Carolina (now the University of South Carolina) in Columbia, from which he graduated in 1825.

After completing his education, Aiken engaged in agriculture as a planter and quickly expanded the family’s holdings. By inheritance and subsequent purchases he came to control Jehossee Island, a large rice plantation on the South Edisto River. Over time, he built it into one of the largest and most productive rice plantations in South Carolina, with over 700 enslaved people working approximately 1,500 acres under cultivation—almost twice the acreage of the next largest plantation. By 1860 he owned the entire island, and Jehossee produced approximately 1.5 million pounds of rice annually, along with sweet potatoes and corn. Aiken resided primarily in Charleston, where his urban residence, later known as the Aiken-Rhett House, became a prominent landmark and is now preserved by the Historic Charleston Foundation.

Aiken entered public life in the late 1830s. In 1830, at the age of twenty‑four, he attended a nullification dinner at which many of his contemporaries offered toasts favoring South Carolinian resistance to federal authority and the possibility of independence. He distinguished himself by offering a toast in favor of the Union, declaring, “The Union—Let not the hasty and ill-timed resistance on the part of the South sever forever the golden links with which we are so beautifully united.” He formally entered politics in 1837 and was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives, serving from 1838 to 1842. He then served in the South Carolina Senate from 1842 to 1844. In 1844 he was elected governor of South Carolina, serving a two-year term from 1844 to 1846. As governor he presided over a period of relative calm in state politics, though the broader national debate over slavery and states’ rights continued to intensify.

In 1831 Aiken married Harriet Lowndes, daughter of Representative Thomas Lowndes and granddaughter of Governor Rawlins Lowndes, thereby strengthening his ties to one of South Carolina’s most influential political families. The couple had one surviving child, a daughter, Henrietta Aiken (1836–1918), who later married Confederate Major Andrew Burnet Rhett in 1862. Rhett was the son of Robert Barnwell Rhett, a leading “Fire-Eater” and ardent secessionist. Through this marriage, Aiken’s family became closely linked to some of the most prominent advocates of Southern nationalism, even as Aiken himself maintained a reputation as a Unionist. Aiken’s extended family was also politically prominent; his first cousin, D. Wyatt Aiken, served as an officer in the Confederate States Army and later as a five-term U.S. Congressman.

Following his gubernatorial service, Aiken was elected as a Democrat to the United States House of Representatives. He served in the Thirty-second, Thirty-third, and Thirty-fourth Congresses from March 4, 1851, to March 3, 1857, representing South Carolina in the U.S. Congress during a critical period in American history. In the House he contributed to the legislative process over three consecutive terms, participating in debates that reflected the growing sectional divide over slavery, territorial expansion, and federal authority. In December 1855, during the organization of the Thirty-fourth Congress, Aiken emerged as a leading candidate for Speaker of the House. The contest dragged on for two months and required 133 ballots before Nathaniel P. Banks of Massachusetts prevailed over Aiken by a vote of 103 to 100. This protracted struggle has been characterized as “the longest and most contentious Speaker election in House history.” In 1866, while South Carolina was under a provisional governor during Reconstruction, Aiken was again elected to represent his district in the Fortieth Congress, but he was not seated.

Aiken’s political stance during the secession crisis and the Civil War reflected his long-standing Unionist convictions. In an 1865 interview he stated, “No, I have never cast my lot with them (the secessionists). I told them they were wrong from the first. I gave a toast for the Union at a nullification supper in 1830, and offended all my young associates, and since the rebellion commenced I have not been to Richmond or Montgomery, and have declined office from Mr. Davis (President of the Confederacy) for myself and friends.” He recounted that when Jefferson Davis was his guest in Charleston, he defended the Union and rejected the doctrine of secession. Aiken further reflected that “these have been four dreadful years,” adding that he had warned secessionists of the devastation that war would bring and had only been mistaken in predicting that the Confederacy would be conquered in two years rather than four. Throughout the American Civil War he remained a loyal Unionist, though he did not take up arms against the Confederacy and many of his friends and relatives were ardent secessionists.

As a major slaveholding planter, Aiken’s wealth and influence rested on the labor of enslaved people, yet contemporary and later accounts distinguished his treatment of enslaved workers from that of some of his peers. Following the Dred Scott decision in 1857, he began spending summers in more temperate Northern locations, traveling with some of his slaves. During this period he became an early patron of the University of Minnesota, extending loans totaling about $28,000, a sum roughly equivalent to $750,000 in 2016 terms. After the Civil War and emancipation, Aiken adapted quickly to a system of paid labor and expanded his business operations. Unlike many Southern landowners who turned to sharecropping or debt peonage, he reportedly paid his formerly enslaved workers wages every Saturday. In an 1863 interview, Robert Smalls, a formerly enslaved man who later became one of the first African Americans elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, remarked, “The only person down here who treated his people well was Governor Aiken. He gave them everything they wanted.” Another formerly enslaved man, Elijah Green, contrasted Aiken with a notoriously cruel slaveholder, saying in a 1930s interview that the latter “was the opposite to Governor Aiken who live on the northwest corner of Elizabeth and Judith streets.”

The war nevertheless inflicted heavy financial losses on Aiken. He claimed that demoralized protectors of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Beaufort sent a gunboat to his country home on Jehossee Island and looted it of its remaining furniture and treasures. According to a northern interviewer, “the governor’s favorite sideboard stands in the house of a citizen of Boston, as a relic of the war.” Aiken estimated that he had lost nearly all his property—some seven or eight million dollars—but added that if he had retained enough for his support, he would not mourn the loss. Despite wartime devastation, the Jehossee Plantation regained much of its preeminence in the postwar years, producing about 1.2 million pounds of rice. Over time, descendants of the Aiken family, the Maybanks, continued to own part of Jehossee Island, selling the remainder in 1992 to the United States government as part of the ACE Basin National Wildlife Refuge.

In his later years, Aiken divided his time between Charleston and summer retreats in the mountains. He continued to be regarded as a significant figure in South Carolina’s political and economic life and remained associated with the Democratic Party and with efforts to rebuild the state’s economy after the war. His Charleston residence, the Aiken-Rhett House, survived as a major example of an antebellum urban plantation complex. The Honors College at the College of Charleston is housed in a building constructed by Aiken in 1839, reflecting his long-standing architectural and civic imprint on the city. On September 6, 1887, William Aiken Jr. died at Flat Rock, North Carolina. His body was returned to Charleston, where he was interred in Magnolia Cemetery. In October 2020, amid broader efforts to address diversity, equity, and inclusion, the College of Charleston removed Aiken’s name from its Honors College top scholars program, renaming the “Aiken Fellows Society” as the “Charleston Fellows.” College President Andrew Hsu linked this decision to ongoing institutional initiatives on inclusion, and the change was welcomed by campus diversity leaders. The Office of Institutional Diversity at the College was later reorganized in March 2025, with its functions integrated into other areas of campus administration, while the building Aiken constructed in 1839 continued to serve as the home of the Honors College.